Bayesian Accountability & Autonomous Systems: A Potential Framework Addressing Evidentiary and Causality Challenges in Tort Law

The Problem

Autonomous systems present tort law with a structural epistemological barrier that existing legal mechanisms struggle to overcome. Morgan (2024) identifies the core difficulty: system characteristics such as "complexity, opacity and autonomous behaviour" render traditional fault-based liability problematic, particularly concerning proof of causation. The opacity problem—what Bathaee (2018) terms "the artificial intelligence black box"—means that even system designers often cannot explain why a machine learning model made a specific decision. This creates what the Expert Group on Liability and New Technologies (2019) characterises as a situation where "identifying tortfeasors or where the costs should lie is highly complex" due to connectivity, data sharing, opaqueness, and the multiplicity of parties involved in development and deployment.

The evidentiary burden on claimants becomes prohibitive. Victims face what Morgan (2024) describes as information asymmetries that are expensive to overcome, "particularly acute in lower value cases." The problem compounds when systems learn post-deployment, since "the system that was certified safe might have 'evolved' by the time of the accident" (Hervey & Lavy, 2021). Lehmann et al. (2004) and Karnow (1996) have documented how distributed AI architectures fragment causal chains across multiple actors and computational processes, rendering traditional causation analysis intractable.

The European Commission's proposed AI Liability Directive attempts to address these difficulties through rebuttable presumptions of causation and rights to evidence disclosure (European Commission, 2022). However, as Morgan (2024) observes, these mechanisms "fail to solve many of the core problems of AI liability" including "problems concerning duty, fault, remoteness and 'many hands'." The disclosure obligation, even where implemented, "does not address the problems that the claimant will have in interpreting [complex technical data] and identifying fault." Common law jurisdictions with existing disclosure regimes face similar difficulties. The fundamental issue is not procedural but infrastructural: accountability cannot be reliably reconstructed ex post from systems designed without ex ante provisions for interpretability.

A Potential Technical Approach: Bayesian Accountability Infrastructure

One possible direction for addressing these challenges reconceptualises liability determination as a real-time inference problem amenable to principled probabilistic treatment. Rather than attempting to reverse-engineer opaque decision processes after accidents occur, this approach would embed auditable probabilistic reasoning into autonomous systems from deployment. Three integrated components might transform the evidentiary landscape:

Continuous Evidential Logging via Bayesian Sufficient Statistics: Rather than storing raw sensor data—which creates storage burdens while remaining difficult to interpret—autonomous systems could maintain compressed probabilistic summaries that preserve information necessary for posterior inference. At each decision point, the system would record: prior probability distributions over environmental states, likelihood functions mapping sensor data to hypotheses, posterior distributions after evidence integration, decision-theoretic quantities including expected utilities and confidence intervals, and detected distribution shifts indicating out-of-specification inputs. This approach draws on the mathematical result that sufficient statistics capture all information in data relevant to parameter estimation, enabling substantial compression without inferential loss. The "black box" would become what might be termed a "glass box"—not by achieving full interpretability of neural network internals, but by exposing the probabilistic reasoning that drives decisions.

Causal Graphical Models as Forensic Infrastructure: Pagallo (2013, p. 138) notes that "even the best-intentioned and best-informed designer cannot foresee all the possible outcomes of robotic behaviour." However, explicit causal structure can be maintained even when specific outcomes cannot be predicted. Systems could implement causal Bayesian networks representing the generative process from environmental conditions through sensing, inference, decision, and actuation to outcomes. When incidents occur, counterfactual queries become computable using the do-calculus framework developed by Pearl (2009): P(harm | do(alternative_action), observed_evidence). This directly addresses the causation problem identified by Bathaee (2018)—rather than constructing narrative arguments about whether a defect "caused" harm, adjudicators could evaluate quantified counterfactual probabilities against legally defined thresholds. The approach would operationalise what Lehmann et al. (2004) describe as the need for formal causal reasoning in AI liability contexts.

Uncertainty-Aware Behavioural Envelopes. Burton et al. (2020) define autonomous systems as those which "make decisions independently of human control" and note the spectrum from fully autonomous to advisory systems. For liability purposes, manufacturers might certify not point-estimate performance claims but full predictive distributions over system behaviour conditional on operating conditions. Such envelopes would specify: epistemic uncertainty (reflecting limitations in training data and model knowledge), aleatoric uncertainty (irreducible environmental stochasticity), and calibration guarantees (that stated confidence intervals achieve nominal coverage rates). Incidents could then be classified by whether they fell within certified uncertainty bounds—distinguishing statistically anticipated failures from systematic miscalibration that might indicate defective design or inadequate testing.

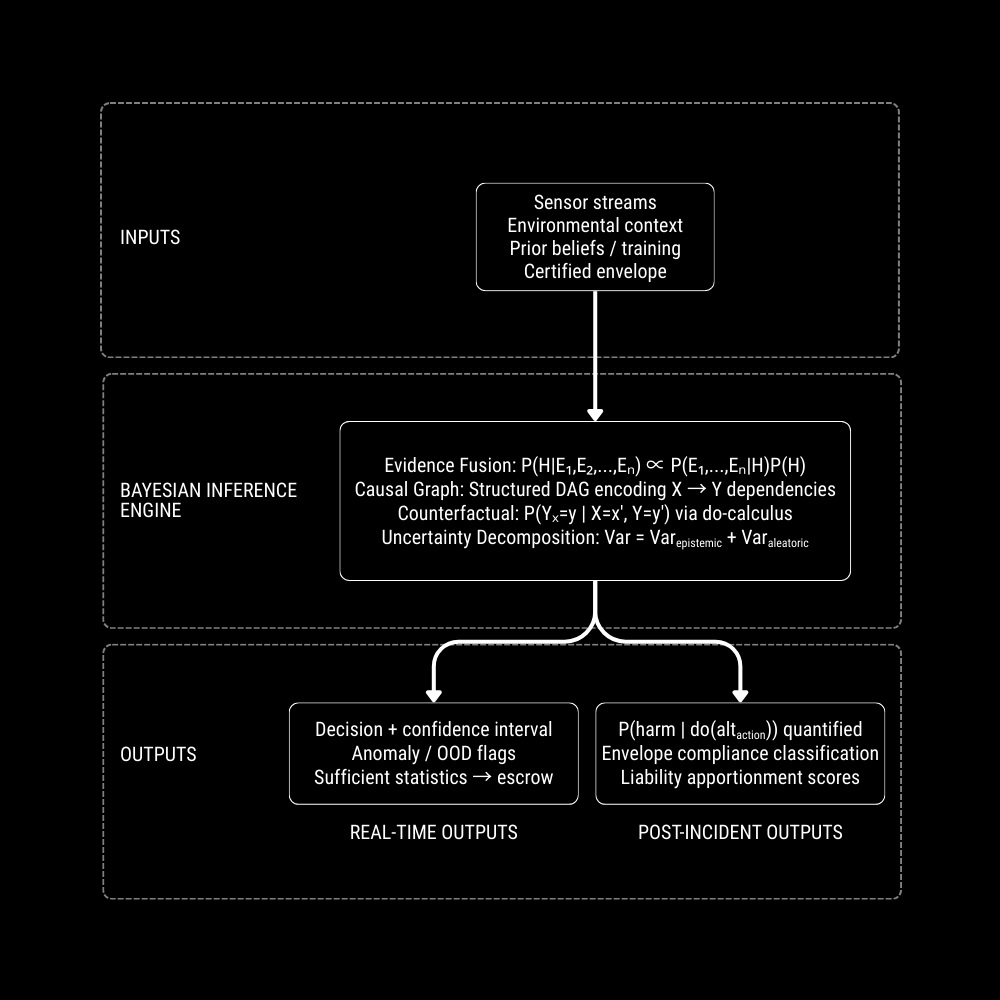

Framework Architecture

Figure 1: Bayesian Accountability Infrastructure for autonomous systems liability. The framework transforms liability determination from post-hoc narrative reconstruction to real-time probabilistic inference: heterogeneous inputs (sensor data, environmental context, certified behavioural envelopes) flow through a Bayesian inference engine performing evidence fusion, causal reasoning, and uncertainty decomposition, producing both operational outputs (decisions with calibrated confidence, anomaly flags, escrowed sufficient statistics) and forensic outputs (quantified counterfactual probabilities, envelope compliance classifications, liability apportionment scores) that map directly onto tort law's evidentiary and causal attribution requirements.

Legal Integration Mechanism

Such a framework could transform liability adjudication from adversarial narrative construction to structured probabilistic evaluation. Adjudicators would receive quantified outputs: the posterior probability that the system operated outside its certified envelope; the counterfactual probability that harm would have been avoided under alternative decisions; and calibration diagnostics indicating whether manufacturer uncertainty claims proved accurate. This responds to Morgan's (2024) observation that "potential industrial users of such technologies... appear to be highly aware of the potential for accidents" and that "resultant liability concerns are a major barrier to the adoption of such technologies"—predictable, quantified liability exposure could reduce uncertainty for both deployers and insurers.

The approach might address the burden of proof difficulties that Morgan (2024) identifies as rendering the EU's proposed mechanisms inadequate. Burden allocation could become mechanical: complete logs trigger standard causation requirements; corrupted or absent logs shift presumptions toward the victim proportionally. This creates what Ericson et al. (2003) term "insurance as governance"—strong incentives for transparency without requiring adversarial discovery processes.

Critically, the framework could preserve what Morgan (2024) terms "tech-impartiality": the principle that "tort should neither encourage nor discourage the use of new technologies" and that "a pedestrian injured by a collision with a vehicle driven in a manner which falls below the standard of that of the reasonable driver has their right to bodily integrity violated whether or not the vehicle is autonomous or driven by a human driver." Bayesian sufficient statistics encode decision-relevant information at comparable granularity to witness testimony and physical evidence in traditional cases—the victim's evidentiary position would be equivalent regardless of whether the tortfeasor was human or autonomous.

The approach also accommodates the sector-specific variation that Kovac and Baughen discuss in Morgan's (2024) edited volume. Different industries—maritime, medical, oil and gas extraction—face distinct regulatory regimes and risk profiles. The Bayesian framework is parametric: envelope certification requirements, counterfactual probability thresholds for causation, and calibration standards could be adjusted sector-by-sector while maintaining consistent underlying infrastructure.

Limitations and Open Questions

This framework remains speculative and would face substantial implementation challenges. Technical feasibility depends on advances in several active research areas: scalable sufficient statistic computation for deep learning systems, tractable causal discovery in high-dimensional settings, and robust out-of-distribution detection. Legal integration would require careful specification of probability thresholds—what counterfactual probability suffices for causation?—that may resist principled determination. The "many hands" problem identified by Reed (2018) and the Expert Group (2019) is mitigated but not eliminated: causal graphs apportion responsibility but require agreement on graph structure. Whether such infrastructure would survive adversarial gaming by sophisticated manufacturers is unclear. These difficulties warrant serious attention before any implementation could be considered.

References

Bathaee, Y. (2018) 'The artificial intelligence black box and the failure of intent and causation', Harvard Journal of Law & Technology, 31, pp. 889–938.

Burton, S., Habli, I., Lawton, T., McDermid, J., Morgan, P., & Porter, Z. (2020) 'Mind the gaps: Assuring the safety of autonomous systems from an engineering, ethical, and legal perspective', Artificial Intelligence, 279, 103201.

Ericson, R., Doyle, A., & Barry, D. (2003) Insurance as governance, University of Toronto Press.

European Commission (2022) 'Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on adapting non-contractual civil liability rules to artificial intelligence (AI Liability Directive)', COM(2022) 496 final.

Expert Group on Liability and New Technologies (2019) Liability for artificial intelligence and other emerging digital technologies, European Union.

Hervey, M., & Lavy, M. (2021) The law of artificial intelligence, Sweet and Maxwell.

Karnow, C. (1996) 'Liability for distributed artificial intelligences', Berkeley Technology Law Journal, 11, pp. 147–204.

Lehmann, J., Breuker, J., & Brouwer, B. (2004) 'Causation in AI and law', Artificial Intelligence and Law, 12, pp. 279–315.

Morgan, P. (2024) 'Tort liability and autonomous systems accidents—Challenges and future developments', in P. Morgan (ed.), Tort liability and autonomous systems accidents, Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 1–26.

Pagallo, U. (2013) The laws of robots: Crimes, contracts, and torts, Springer.

Pearl, J. (2009) Causality: Models, reasoning, and inference, 2nd edn., Cambridge University Press.

Reed, C. (2018) 'How should we regulate artificial intelligence?', Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 376, 20170360.